- Home

- Bethany Pope

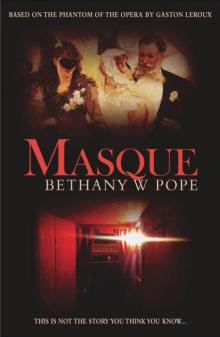

Masque

Masque Read online

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

CHRISTINE

ERIK

RAOUL

CHRISTINE

ERIK

RAOUL

CHRISTINE

ERIK

RAOUL

CHRISTINE

ERIK

RAOUL

CHRISTINE

ERIK

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Copyright

BETHANY W POPE

MASQUE

Every writer has a monster in them. Some are very beautiful. This novel is for all of them.

CHRISTINE

1.

I have everything I ever thought I wanted: a room of my own made for opera, a voice to fill it, a brazier to warm the air and my throat, and a door that locks – the outside painted with a version of my name enclosed inside a star. The mirror is beautiful but that’s all, a rococo frame, gilt around a smooth surface; like so many operas.

I live for the high notes; I serve the occasional glorious aria that redeems a base plot. My voice brings life to the story; my face makes the room seem populated. There are three faces in the mirror and I am looking at them. I am alone and not alone.

The features are a little blurred; they don’t look like they belong to me. The flaws in the right and left wings (beneath the fat and leering putti that glower from the frame) make the sides seem warped. The glass bulges out so that my cheeks might belong to a skull, scraped to bone. Only the front view is clear, recognisable, a dark-eyed, dark-haired woman who must, every night, resemble a girl. Not just any girl but the black-eyed thing I was twenty years ago. It’s funny how much a change in angle, in perspective, warps something that should be so simple. It’s funny how stasis can look so beautiful, so calm at a distance and be so monstrous up close.

The girl knocks. I cannot for the life of me remember her name. Some ballerina rat doing double duty as dresser, as I did once. I rise to admit her. The pink silk frock that Fiordiligi, the Lady from Ferrara, wears in Così fan tutte rustles at the elbows. Locks never work for me but it comforts me to use them. I let her in. A thin-faced blonde, her dancing shoes already strapped, the satin safe behind chamois savers designed to keep the delicate soles from scuffing. As if anything could save our souls. She looks like poor Little Meg, a girl I knew once and haven’t thought of in years. No. That’s a lie. I see her every day. She takes her turn in the mirror, with all the others I’ve loved.

This girl, whoever she is, twitches her nose at me. She might be smelling the blood in my neck – or some other, less mentionable, middle-aged woe.

‘La Changy?’ Her voice is rough, trained she might make a mezzo. As it is, she sounds like a whore with a cough.

‘Yes?’ I am spared impropriety; it would be unfitting if I knew her name. Divas should never nurse rats, should never take the ugly (the ordinary) to their breasts.

‘The new manager, Mr Andre, send his regards. And some new perfume.’

The name makes me start, but there are only a few families wealthy enough to found operas in Paris. The bottle is huge, blown glass, indigo flowers. It would be unpolitic not to wear it. He would notice if my throat smelled only of my artistic sweat.

I nod to the rat, the girl. I have just remembered her name. ‘Apply it, Juliette. A drop.’

Her smile is hideous. Her teeth are yellow and few. She will be a dancer until she drops. Those incisors of hers might save her from syphilis. If so they only seem like ugliness. They have softened me to her. I bend down, almost bowing. I can feel her meaty, spoiled breath on my skin, overpowering the scent of opal fruit and ylang ylang flowers. The glass applicator is cold and wet. It feels like she is tasting my jugular, waiting for me to start feeding her.

Tonight I will leave her a good tip.

2.

I was a lucky rat. The countess who buried my father only looked like an icicle. Her clear skin and white hair concealed a good heart. I do not say a ‘warm’ heart. Everyone alive has one of those lying, fluttering monsters. She was a good mistress, unchristian in her desires but Christian in her dispersal of them. She did not keep me as a lover, as wealthy people (even women) could do then, but she held me as her ward. I had a bedroom in her house just beyond the servants’ quarters. I didn’t have to lodge at the opera house and pay for the privilege of studying there with the sweat of my body. I didn’t have to buy my food by wrapping my thighs around some rich gentleman’s waist. Her kindness saved me from disease, and splinters.

Of course I was lonely. I had status among the other dancers because of her money and my sweet smell, but they hardly spoke to me if they could avoid it. After all, what subjects did we share? I was not hungry. Aside from that, I worked as a chorister.

My voice, at first, was less pure than it had been when I still sang for my father, but enough quality remained for me to sing small roles; a second sister, a Maying maid. They actually paid me for that, on a sliding scale, depending on the take in the production. Of course the regular singers had little to do with me, except for the sessions I spent learning from the Music Master (the countess paid for those). It would have been improper for a cast member whose art was ‘pure’ to speak with a singer who also worked as a dancer.

Little Meg was an exception. Her face was thin, and hollow (she sold her teeth to buy her mother free from jail) but she was a beautiful dancer. She was the highest-paid member of the company who wasn’t a musician or a singer, even surpassing the salary of La Sorelli – the beautiful girl who enjoyed the affection of the Opera House owner. Little Meg had been educated a bit before her father left, she’d learned to read, and she paid for her lessons by selling painters the privilege of placing her image on canvas.

She was a wonderful conversationalist. I never met a girl with more fondness for books. Once I’d worked around her lisp we had some beautiful talks. I brought her story books after I was finished with them. It was good to feel needed and it reminded me of the time I spent with Father before he died.

She would come in post-production, help free me from whatever lousy wig they’d put me in, and check behind my ears for nits. Then I’d help her clean the wounds on her feet, scrape the scabbing blood from the satin shoes she was still paying the company for and afterwards we would crouch together by the fire and eat some bread, some good camembert (she softened the crusts of her rolls in a mug of warm wine) and we would burn the energy of performance out in conversation. There were never words enough, or time. I still miss her, even now, after everything. I still listen for the sound of her breathing in the dark.

3.

The Opera House was built like a skull beneath the skin, ugly bones beneath some beautiful flesh. The part the public saw was like my mirror, all gilt wood and plush. Behind the scenes the wood was rougher, with the mechanics of scenery flitting (and occasionally grinding) like thoughts. The flies were filled with ragged men who stank and cursed as they drew the ropes. The dressing rooms reeked with the stench of feet and foul water from the pots, the few sticks of furniture were feathered with piles of sodden costumes waiting to be cleaned – the fresh ones were delivered weekly from the cleaners – and since we used them in common (unless we had a named role) the fabric was always slick and clammy with sweat that was only occasionally our own.

Only the big stars, La Carlotta, Senior Piangi, Monsieur Jacques, earned their own rich rooms. The one I have now is nicer than theirs ever were – plumbing has improved since then, and the only bottom to warm my sofa is my own – but back then they were heaven beside what we knew. Oh, how I envied La Carlotta’s silken walls! Now I know that the brilliant colour of the yellow wallpaper had been set with arsenic, but I only saw the surface then, and it was as glorious as her own pampered flesh.

It is amazing that it did not kill her, or her appetite. Every night after she performed she would sit down to a supper large enough to feed a small family. Until she’d had it, she was unfit to meet the public. No matter how adoring they were, how many gifts they gave her, she would snarl at them if she hadn’t had her bread and meat.

La Carlotta was as famous for her bosom as for her silk-sweet larynx. When she hit those high notes in, say, the aria that Elisabeth sings in act five of Don Carlos, the heaving was magnificent, just this side of decency. She padded them, boosted her bosoms with rolled cotton bolsters to preserve their fine shape. I know that now (and I’ve mastered that trick myself) but the effect from the stage was not to be missed.

I saw those fatty flesh-waves when it was my job to turn her out before a show and I had to wedge her into stays made for a smaller-figured woman. How she sang like that, and looked so delicate, I will never know. Off stage she walked with a heavy thump, the flesh of her thighs and buttocks wobbling on her narrow ankles. Say what you will, the woman had style and style is sister to art, and she practised intensely for five hours a day, eating like the workhorse she was between the rehearsal and the show.

We all took turns acting as her dresser. It was good work. The diva screamed a lot when things weren’t perfect, but after she had eaten something she often repented and would leave a good tip. Of course, once the trouble began she rarely tipped me.

She would sit terribly still as I freed her coarse black hair from the pins that bound to her braids those yellow silk strands that some poor woman had sold to the wigmaker, her face pale and moist as fresh dough. It was almost as though she feared I would bite her. It took me years to work out why. She was right to be afraid. She knew what time was; I had no knowledge of it.

ERIK

1.

My father was a master mason. I never met the man but I spent the first decade of my life inside the house he built and so I feel I know him. The lathes of the attic communicated with me as much through their shape (he was exacting when he laid out the angles of the eaves) as did the notations he left in pencil on the undersides of the unfinished, unpainted struts which supported the ceiling. I inherited the crabbed handwriting he used to mark out his measurements, though I am far more articulate than he ever was in artistry, architecture, or print.

Although he was skilled with the trowel and could lay travertine so tightly that its texture was more like marble than limestone, he was more renowned for the beauty of his person that the skill of his hands. He won my mother with his looks and he left her a sad ghost of the gay girl he married, haunting the house that he built on Rue Rouge.

I learned about him through the letters he left to my mother, retained by her in memory of their apparently passionate courtship. They were bound by a blue ribbon, an appropriate memento of an innocent girl. One envelope contained a bright lock of hair that must have been his, since mother’s was as dark as a sewer rat’s. The letters were naïve, almost innocently crude. They were full of phrases about the things that he wished that he could do to her body and peppered with prayers for many years of marital bliss. They were written in the kind of cheap ink that an uneducated man would favour. He did not expect them to last, or be held on to. The sepia was grainy and badly mixed, this combined with his handwriting in such a way that it seemed as though his words were written out by a sexually precocious child with a fondness for experimenting with matchsticks. As I said, my handwriting is no better, but at least the ink I use is superior.

I always thought that writing was a bit like the telepathy those spiritualists in the paper are always talking about. It makes sense, if you think about it; one mind communicates to another through a series of black blotches which transmit thoughts directly into another’s brain. You, reading this, whoever you are, can hear my voice (a sweet, trained tenor) without ever having to worry about viewing the flesh that produces it. This is lucky for you: all my gifts are internal.

In any case, my current habitations remind me of my childhood home. These damp vaults are rather like the basement where my mother moved my crib once the neighbours complained that my cries disrupted their business. The house my father built was tall and narrow, the walls of dark grey granite, polished to the high shine of gravestones. He meant his home to be a living monument to his skill and a permanent advertisement for his services.

The roof was tiled with slabs of greenish slate, and the windows were small and imperfectly glassed. When I was older, I replaced them as a gift for my mother. I spent a whole afternoon removing the warped and watery panes, replacing them with sheets I’d poured myself. I learned the art of glazing, sneaking every night to the factory down the street. When the time came that I had spent enough hours watching the midnight production shift pouring the sheets of reddish molten sand into the mould, I tried my hand at it myself. I waited until the Michaelmas holiday and stole the machinery (I provided my own materials, lugging bags of silicone that I’d found in the cellars among the unopened bottles of wine and the skeletons of rodents). I love the look of glass as it is being poured. It is honest, then, about itself. Cooled, it only seems a solid. It never fully hardens. Over centuries, window glass will melt.

There is no such thing as stasis.

In any case, my mother loved the finished product; windows that let the light in without warping what she saw on the street. She was so thrilled she squeezed my upper arm through the thick fabric of my jacket. I swear she almost hugged me. In any case, for once she did not shudder at my smell or flinch away from the feel of my corpselike body.

The houses on either side of ours were dedicated, in their own way, to music. Dancing girls and cabaret, absinthe and cheap champagne that the likes of those poets who styled themselves ‘Romantic’ drank themselves to death in. My widowed mother hired men to refurbish the attic into a series of rooms that she furnished with sticks she’d bought from brothels, closed in raids by the province governor the previous summer. She did not sleep on them and rarely bothered to change the sheets, so she didn’t have to worry about bedbugs. She made a good living, I must say, giving the drunks who seethed from her neighbours in the early morning a bed off of the streets.

For my fifth birthday she made me my first (and for a long time only) birthday present; a mask cut from a length of chamois that she bought from a glover. It was more like a loose sack with holes cut for eyes than a proper garments but it did its job well. The sight of me ceased bothering her. As I grew older, she let me come up more frequently – although once she had a steady stream of lodgers I never had the run of the attic again – my father’s writing was long since buried behind plaster. I wore the mask without complaint – it was far from uncomfortable and it had a nice smell, as did the sachets of mint and violet that she sewed into my clothing. If she almost never touched me, she did love me as best as she was able, being young and easily frightened.

After a few years of proving my capacity with panes of glass and basic home repairs, she hired a blind tutor to teach me letters, music, mathematics. He would come and sit for hours in my basement room, complaining of the effect of the chill on his bones and making me memorise many disparate packets of learning. When I surpassed his ability to teach, as I soon did, I had many books close at hand and I turned to them to expand my knowledge. I read everything from Archimedes to fairy stories. As I recall, I had a special affection for La Belle et la Bête. My mother bought me as many books as she could afford through mail-order – often secondhand. She resold them after I had squeezed them of their nutrients, though I demanded permission to keep the fairy tales. They were a balm to me, with their stories of transformation. They provided me with a sharp and dangerous hope.

I could read as much as I liked, as long as I remained hidden. It would not have done for me to frighten the lodgers. I was happy, very happy, while I had enough books and candles. I do not believe that anyone but mother and the old tutor knew that I was still alive. The neighbours probably believed that I died in infancy. It cer

tainly would have been safer for Mother to spread that rumour, given the prevalence of local superstition and a widespread belief in ‘changelings’.

When I turned thirteen, she sent me to school.

2.

I lived for five years with the Sisters of the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul. They were known locally as the ‘Grey Sisters’ because of their granite-coloured habits and starched white veils that rose into peaked horns from the sides of their heads. These nuns ran a school for the troubled gifted (a category that fitted me like a glove) where they provided care for the physically weak and specialised learning for the intellectually advanced. The school was founded in 1640 near the centre of the city but disbanded after the failed revolution – the nuns hid while the trampled and impoverished citizens that they’d once fed hosted gallows-staged puppet shows with the decapitated corpses of their oppressors.

One extremely elderly lady was a novice at the time when Reason reined from her bloody throne. She sat crouched in her chair (carved from the unbroken trunk of a thorn tree) and muttered horrors to us while her rheumy green eyes blazed from the loose folds of her face.

‘You think that you’ve known terror, child?’ Sister Mercy leaned in close to me, her nose brushing the kid mask above the place my nose was not.

I nodded at her, silent. I was conscious of the effect that my voice had on women. The mixture of attraction and repulsion that I provoked when I spoke would have been alarming to see in a nun – especially a virgin lady who had lived so long as to be nearly able to match me in ugliness.

She laughed, a sound like a frog caught in a sausage-grinder. A connoisseur of sound even then, I stored it away for future reference, to practise at my leisure. I sat on my heels, listening in the ashes of the stove.

‘Well, child, you haven’t seen anything until you’ve seen the rotting corpse of a sixteen-year-old virgin hung from ropes hooked into her thighs, above the knees, her wrists, and the ragged stump of her neck so that she can be made to act out a play by that old rascal Robespierre. I saw this many times, starring different ladies of course. The puppets could hardly be made to last beyond a few performances. The stench would get too bad, the muscles would liquefy so that they slid from their hooks like a soft-boiled egg strung on a wire. They’d smell worse than you do, you little living corpse.’

Masque

Masque